“Since everything today is valid or invalid only as determined by the dictatorship of ‘publicness,’ which is a function of technology, it may be impossible for centuries to come for what is essential and original simply to allow itself to unfold.”

Martin Heidegger

Letter of March 21, 1948, to Elisabeth Blochmann, in Martin Heidegger and Elisabeth Blochmann,

Briefwechsel, 1918–1989, ed. Joachim W. Storck (Marbach: Deutsche Schillergesellschaft, 1989).

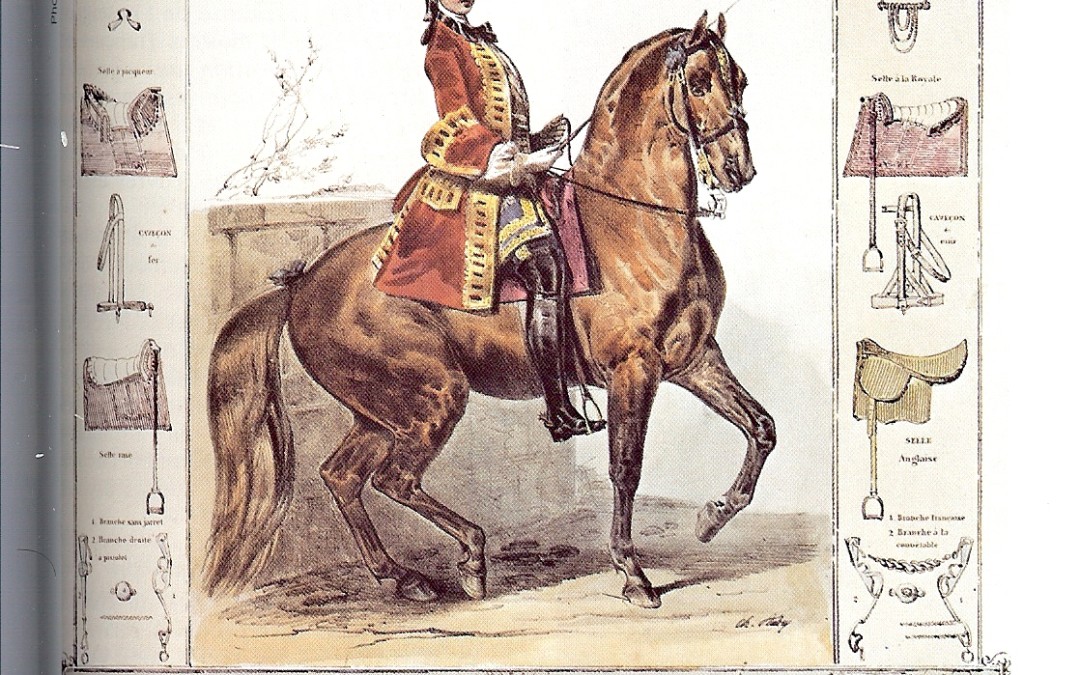

To say that dressage has suffered from the “dictatorship of ‘publicness,” is an understatement. The initial rules for dressage, created by the military elite at the turn of the 20th century where already a drift to “publicness” when you consider the root of dressage in terms of the 18th century nobility. However, the leap of dressage into the public arena which occurred in the latter part of the 20th century profoundly changed the practice of those rules. In an attempt to make the noble art into a public sport took the rules and even the nature of the horse and turned them all upside down.

In a time which better favored dressage, allowing the horse and rider to unfold themselves was part of the process called training. There was a basic willingness and tacit understanding to allow an organic unfolding.

The logical first step in the training of the horse in this organic way is the joining of the two minds. Without such a process, training is reduced to a series of recipes. Of course, dressage, as it exists today, is just that, but it is this way because of complete assimilation by the military.

Having lost the art, the military, rightfully, imposed their training manuals. However, riders of today, do not need to go to war with the horse, unless we consider the world of competition as our new war.

The difference in favor of the restoration of the art lies in the consideration of the horse as a sentient being. When such a feeling for the horse is extended to the horse, we can see that the welfare of the horse becomes the sacred responsibility of rider or owner.

Removed from consideration of the horse as a instrument of the sport, we are brought to a place where the mixing of the two mind, horse and human, becomes a field for intense study which cannot fail to enrich both beings. In seeking the art, we co-create with the horse a living aesthetic experience.

How do we begin such a study and do we throw out the manuals of the past?

The path starts in a calm silence. The manuals and technical knowledge is not abandoned but instead are put aside as we seek to cultivate a deep listening. Such listening is not centered in deep self-centered referencing nor in a referencing which would be described as self-preferential at all. The listening needed is one of strong empathy at its inception but leads to a compassion which experiences the horse as it is.

This ultimate kind of listening is a practice which arises from empathy and a mind free from aggression. This is certainly not the mind of a soldier but the heart of an artist. Throughout history, this has always been the source of all great horsemen.

The calm silence needed to work with the horse is about feeling and being and connecting in sensation, first with space and then through touch. It is in the cadence of energies that are naturally present, such as the breath and the rhythmic movement of the limbs.

Recent Comments